Information on this page about the interventions is based on the book, Prevent-Teach-Reinforce: The School-Based Model of Individualized Positive Behavior Support, Second Edition by G. Dunlap, R. Iovannone, D. Kincaid, K. Wilson, K. Christiansen, and P. S. Strain.

What is the strategy? Why does it work?

Provide a system in which the student monitors, evaluates, and reinforces their own performance or non-performance of specified behaviors.

- Self-management teaches students to be cognizant of their performance of specific behaviors in light of a behavioral goal in a way that allows them to be responsible for the behavior.

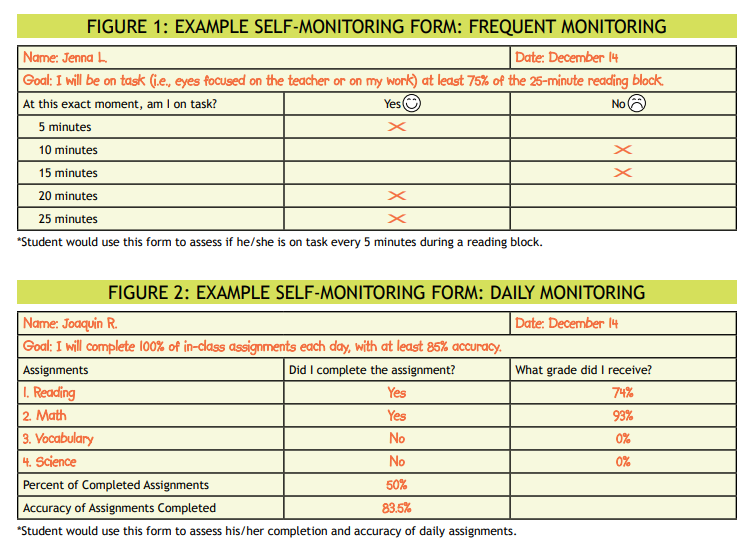

- Self-monitoring is the student recording of their behavior target

- Self-evaluation involves the student comparing their performance with a specified criterion (a behavioral goal or a teacher’s rating).

Teaching students strategies to monitor and manage their own behaviors is vital in enhancing independent functioning. Self-management interventions are effective when paired with a reinforcement for meeting and surpassing goals. There may also need to be a reinforcement process for accurate self-marking of performance. Using the function of the behavior as the reinforcement can be a powerful motivator for students to work toward achieving their goals.

Functions and antecedents the teach self-management intervention works for

If the challenging behavior occurs…

- To gain teacher or adult attention

- To escape or avoid a non-preferred task or activity

- To delay a transition from a preferred to non-preferred activity

- When academic demands are requested of the student

If the intervention goal is to…

- Increase the rate of positive behavior, such as attention-to-task or academic productivity

- Increase task productivity

- Decrease rates of inappropriate behavior

Steps for Implementation

Self-monitoring

- Define the replacement behavior to be monitored in operational terms.

- Make sure the definition is observable and measurable.

- Identify the time periods for which the student will self-monitor the behavior.

- Take baseline data during those time periods to establish a criterion that will serve as the initial goal, which can be slightly above baseline performance.

- For example, if the student is currently academically engaged for 50% of the specified time period for self-monitoring, the initial criterion could be set at 60%.

- Meet with the student to talk about the self-monitoring strategy, the goal, and how he/she will monitor the behavior during the specified routine.

- Discuss how the self-management card will be formatted, including student preferences in the design.

- Decide upon the sound that will be used to signal the student that it is time to self-record. When the sound goes off, the teacher will also have a copy of the self-management card to record whether the student was or was not performing the behavior.

- Before using the self-management system, train the student by setting up a simulated situation and practicing recording occurrences and non-occurrences of the target behavior.

- Be sure to practice “gray” areas so that the student knows the exact expectations of the behavior.

- Decide upon the reinforcement to be earned when the student meets the established goal.

- Consider the function of the challenging behavior in developing the reinforcement system

- Select a way of reviewing the student’s self-management recordings and assisting with student evaluation of his/her performance.

- Deliver the reinforcement when it is earned.

- Develop a plan to gradually shape performance.

- This can be increasing the criterion by incremental units (e.g., 10% increase each week).

Self-Evaluation

- Follow all of the steps of self-monitoring. Self-evaluation helps the student become increasingly independent in evaluating his/her own performance.

- At the end of the routine for self-monitoring, the teacher and student will compare their evaluations of the student performance.

- If the student’s ratings are an exact match or close match (e.g., within one recording check error over or under the teacher’s ratings), the student earns a reinforcer.

- This reinforcer can be an additional one to the one for meeting criterion or it can take the place of the criterion reinforcer.

- If choosing to do the second, be aware that students may discover a “loophole”. That is, the student can perform lower than the goal but still get reinforcement as long as their ratings agree with the teacher’s ratings.

- This reinforcer can be an additional one to the one for meeting criterion or it can take the place of the criterion reinforcer.

Additional Considerations when Implementing

- The process should be clearly explained the student and appropriate recording and cueing systems should be selected.

- The student should be involved, as much as possible, on decisions related to the self-management system including behavioral criteria, format of the self-management form or card, timer type to be used to prompt for ratings, etc.

- Always use self-management with a reinforcement system. If the self-management system is not showing effectiveness, it may be due to the reinforcement not being delivered when the student meets the goal or the reinforcement not being motivating enough to elicit the desired performance from the student.

- A plan for fading teacher prompts should be included once the student is reaching criterion.

How to implement this strategy in multiple ways (examples & resources)

- Intervention Central How To – Includes step-by-step overview for intervention and examples of forms for students to collect self-monitoring data on

- Rating Scale form

- Behavior Checklist form

- Frequency Count form

- Self-Monitoring Webinar (19:15) – This webinar in the Strategic Behavior Intervention Series explains the core components of self-monitoring programs, how to collect data for effectiveness, how to overcome potential pitfalls, and resources for future use.

- Countoons – An example of one type of self-monitoring system for young students. Brief video explanation (2:30) is also provided. A 6 page article about the intervention and how to use it is also available.

- Self-monitoring article from LSU – This article includes an overview of self-monitoring, treatment integrity checklists, and a detailed vignette of the strategy being implemented with a third grade student.

- Self-monitoring data collection examples – This website provides several examples of different types of data collection forms for self-monitoring in different areas, including behavior, engagement, expectations, and more.

- Self-monitoring module from the Iris Center

- Self-management EBP Brief Packet – Includes an overview of the intervention, evidence base, step-by-step guide, implementation checklist, data collection sheet, tip sheet for professionals, parent guide, and more resources

- Self-monitoring form examples (from Project Support & Include at Vanderbilt University)

Tips for Self-Monitoring During Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (adapted from table in Menzies et al., 2009)

- During development of self-monitoring procedures

- If possible, train and implement at the beginning of a school year or semester (Glomb & West, 1991).

- Address one positive behavior at a time. Select the behavior earliest in the chain (Vanderbilt, 2005). For instance, monitor academic productivity instead of time on task (a student must be on task to be academically productive).

- Use the positive of the behavior (often the replacement behavior); instead of having a goal to decrease time off task, have the student monitor time on task (www.Lehigh.edu/projectreach/teachers/self-management/sm-implement.htm).

- Consider a preintervention functional assessment for a full understanding of underlying interactions between behaviors and environment to increase efficacy (Dunlap et al., 1995).

- Create a package that can be used along with instead of replacing existing classroom management practices (Dunlap et al., 1995)

- While teaching the student self-monitoring procedures

- Secure buy-in on the part of the students. The more a student buys in, the more likely her or she will be to use it (Dunlap et al., 1995).

- Use the student’s strengths and examples of his or her performance of desirable behavior to describe the procedure (Vanderbilt, 2005).

- Have a student-friendly definition of the behavior being monitored on hand. Be sure to use observable terms and include examples and nonexamples (Vanderbilt, 2005)

- During implementation

- Give consistent, behavior-specific verbal praise.

- Student materials should be inconspicuous and age appropriate, with teachers using the least cueing possible (Carr & Punzo, 1993).

- Use data to monitor and reward honesty of self-recording as well as improved performance(Project REACH, 2008; Dunlap et al., 1995).

- Use self-graphing or weekly charts (Carr & Punzo, 1993).

- Provide high levels of support/prompting at the start of implementation and then fade for generalization.

Supporting Research

Axelrod, M. I., Zhe, E. J., Haugen, K. A., & Klein, J. A. (2009). Self-management of on-task homework behavior: A promising strategy for adolescents with attention and behavior problems, School Psychology Review, 38(3), 325-333, https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2009.12087817

Briere, D. E., & Simonsen, B. (2011). Self-monitoring interventions for at-risk middle school students: the importance of considering function.Behavioral Disorders, 36(2), 129–140. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43153530

Briesch, A. M., Daniels, B., & Beneville, M. (2019). Unpacking the term “self‑management”: Understanding intervention applications within the school‑based literature Journal of Behavioral Education, 28, 54–77 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-018-9303-1

Carr, S. C., & Punzo, R. P. (1993). The effects of self-monitoring of academic accuracy and productivity on the performance of students with behavioral disorders.Behavioral Disorders,18(4), 241-250. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F019874299301800401

Cohen, D., Briesch, A., & Riley-Tillman, T. C. (n.d.). Self-management [Intervention brief]. University of Missouri, Evidence Based Intervention Network. https://education.missouri.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2013/04/Self-Managememt-Brief1.pdf

Howard, A. J., Morrison, J. Q., & Collins, T. (2020). Evaluating self-management interventions: Analysis of component combinations. School Psychology Review, 49(2), 130-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1717367

Kern, L., Ringdahl, J. E., Hilt, A., & Sterling-Turner, H. E. (2001). Linking self-management procedures to functional analysis results. Behavioral Disorders, 26(3), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874290102600304

Koegel. L. K., Koegel. R. L., Boettcher, M. A., Harrower, J., & Openden, D. (2006). Combining functional assessment and self-management procedures to rapidly reduce disruptive behaviors. In R. L. Koegel & L. K. Koegel (Eds.), Pivotal response treatments for autism – Communication, social, and academic development (pp. 245-258). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

Menzies, H.M., Lane, K.L., & Lee, J.M. (2009). Self-Monitoring Strategies for Use in the Classroom: A Promising Practice to Support Productive Behavior for Students with Emotional or Behavioral Disorders. Beyond Behavior, 18, 27-35.

Mooney, P., Ryan, J. B., Uhing, B., & Reid, R. (2005). A review of self-management interventions targeting academic outcomes for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Behavioral Education 14(3), 203-221. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10864-005-6298-1

Rock, M. L. (2005). Use of strategic self-monitoring to enhance academic engagement, productivity, and accuracy of students with and without exceptionalities. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/10983007050070010201